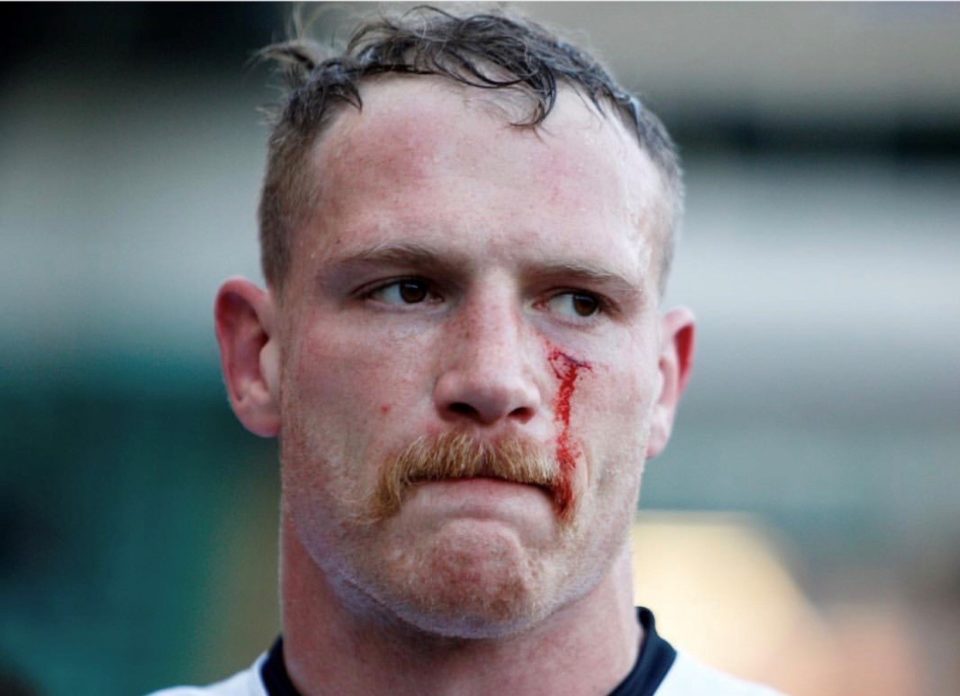

Kearnan Myall, GB Snowsport Human Performance Lead and former professional rugby player, explains the rationale behind the new snowsport head injuries management protocols

It probably feels, for a lot of people, like public discussion around head injuries and concussion in sport is a relatively new thing. Revelations from football, American Football, and my former sport, Rugby Union, have seen a heightened level of press and public awareness – sadly, too often linked to the tragic consequences of traumatic head injuries sustained by athletes.

In truth, the existence of risks around head injuries have been known for decades. It’s only in recent years though, with scientific advances in neuroimaging, that the body of evidence around different forms of head injuries, and different sport-specific conditions have allowed us to gain a deeper understanding of what happens to an athlete when these injuries are sustained.

Skiing and snowboarding may not be the first sports that come to mind when a person thinks about head injuries; contact sports such as boxing and rugby, and those involving regular use of the head – heading in football, for example – have seen far greater awareness about the risks of injury over the past few years. But within skiing and snowboarding, at all levels, mild traumatic brain injuries are actually one of the most commonly reported injuries in the sport.

Improving our athletes’ and coaches’ understanding of the risks associated with head injuries, and their ability to identify them, is key to optimising the medical support we provide. For example, only 1 in 10 concussions results in loss of consciousness, and we know from Rugby Union that the introduction of head injury education helped increase the identification of concussions by three-fold in the following seasons.

This led us to the introduction of new Head Injury Management protocols across all our disciplines. We’ve seen from other sports how serious the effects of repeated head injuries can be, and those are the precise things that none of us wants to see repeated in skiing and snowboarding.

And the truth is, some very fine snowsport athletes have also experienced the seriousness of head injuries, and taken action for the good of their long-term health.

For athletes the risk of injury is an ever present and unavoidable occupational hazard. Speaking as a former professional sportsman myself, you accept these risks, with the understanding that you will be given the best treatment available should the worst happen. Unfortunately, this has not always been the case with regards to head injuries, as the negative consequences are not always immediately apparent. It is imperative, therefore, that our protocols and support systems align with the gold standard medical evidence, even when this means removing an athlete from training and competition for what might be deemed only a ‘minor’ knock.

I understand all too well, from being in the position myself, that it can be deeply frustrating to be told you can’t train or compete due to an injury that you feel isn’t having a major bearing on you. The instinct to dust yourself down and get on with it is a very human one, and is to be expected with elite athletes. Head injuries can be particularly difficult to self-monitor though, not least because some symptoms may not make themselves apparent for up to a week after the injury is sustained. It’s for that reason that we, as a Governing Body, have to take those decisions out of the hands of athletes.

From a performance perspective, once an athlete has sustained a mild traumatic brain injury, they are nearly three times more likely to suffer a physical injury, or a further compounding head injury, so it’s in everyone’s interest for them to recover fully before returning to snow. Introducing these new protocols won’t be a panacea for head injuries in our sport. We are actively seeking investment for snowsport specific head injury research, and are lobbying stakeholders throughout our sport to bring their guidance in line with the latest research. As our understanding of head injuries increases we’ll adjust our protocols and medical care accordingly.

The medical and sports science that sits behind the development of these new measures is something we can be proud of, and the hope is that it will offer reassurance to athletes, coaches, families, and fans of skiing and snowboarding too. We want to make sure we are offering every available support option to strengthen the sport now and in the years to come.

Header Image: Kearnan Myall during his professional rugby career

Share

Share